The Invisible Bar

Discover the importance of the silence before the first bar: the emotional synchrony among musicians, the conductor’s mental preparation, and the power of shared attention in orchestral music.

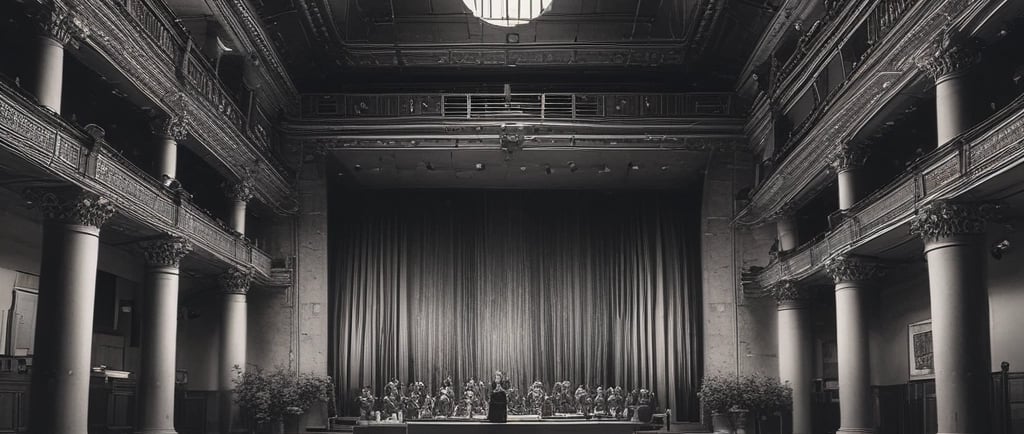

There is a moment, imperceptible yet charged with energy, that occurs before any piece of music begins. That instant when the audience has stopped whispering, the conductor raises the baton, the musicians hold their breath, and the air itself seems to thicken. There is no sound yet, and still, there is music.

That suspended space — that silence filled with intention — is one of the most mysterious and necessary experiences in all of music. It is the silence before the first bar, a territory where music does not yet exist, but is already becoming.

Since the dawn of collective musical practice, that brief instant has carried a ritual meaning. In early Baroque chapels, when musicians gathered around the maestro di cappella, there was no public as we know it today — only a group searching together for the inner pulse of the work. There were no lights, no applause: only shared breathing. Later, as the concert became a public event, that silence acquired ceremonial weight. In the nineteenth century, Wagner wrote that “the initial silence must be as expressive as Tristan’s chord,” and Mahler often reminded his musicians that a symphony began before it was heard — in that moment when the conductor’s gesture had not yet fallen.

Today, in a concert hall, that same silence still carries a sacred weight. It is not merely a pause; it is a pact between the audience and the orchestra, a tacit agreement to inhabit a single stretch of time. Some German halls even have a name for it: Stille der Saal, “the silence of the hall” — an acoustic and emotional phenomenon that occurs when the entire audience realizes that the music has already begun, even though not a single note has yet been played.

John Cage took that idea to its extreme in his famous 4’33’’ (1952), reminding us that absolute silence does not exist. There is always sound: breathing, the creak of a chair, the hum of electricity. But Cage was not speaking only of acoustics — he was speaking of perception, of how our attention transforms noise into music. In truth, the silence before the first bar is not absence, but a form of active listening — the instant when composer, performer, and listener prepare to share the same mental time.

In orchestral practice, that silence fulfills both structural and psychological functions. Before the first bar, players must align mind, breath, and gesture — and that alignment is anything but automatic. A study at the University of Helsinki (Vuust et al., 2014) showed that, in the moments preceding an initial attack, the brains of professional musicians synchronize their alpha and beta waves both with each other and with the conductor’s movements. In other words, the orchestra “connects” neurologically before producing a single sound. That invisible synchrony is what allows a tutti to emerge as one body, what makes the first chord feel like the natural exhalation of a shared breath.

Silence is also the space of intention. At that moment, the conductor is not yet directing sound, but potential time. A breath, a glance, the subtle curve of the baton through the air — these are signals that summon attention and collective focus. One might say that true conducting begins before there is any audible music: in that choreography of minimal gestures where energy is gathered and shared. Claudio Abbado once said that “an orchestra breathes before it sounds, like a living creature.” That common breath is the true bar zero. No score indicates it, but on its quality depend the character of the opening, the tuning, and the emotional energy of the entire performance.

A study from the Vienna Conservatory (Repp, 2013) found that the precision of a musical entrance correlates directly with the respiratory coherence of the group. When everyone breathes in unison, attacks are cleaner, timing more precise. It is a physiological fact — but also a symbolic one: air becomes a bond between wills.

For the audience, too, that moment holds power. The listener is not a passive recipient but part of the acoustic environment the music inhabits. In those few seconds of silence, the brain prepares, adjusts its threshold of attention, and fine-tunes auditory sensitivity. Neuroscience has shown that just before the music begins, the limbic system releases anticipatory dopamine — the same neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and expectation. That is why the silence before the first note can be as thrilling as the sound itself: in it lies the promise of what is about to happen.

The Spanish band tradition, deeply rooted in the communal, has preserved this collective sense of silence. When a banda is about to begin, it does not do so merely because the conductor gives a cue, but because everyone feels that the moment has arrived. It is not only a matter of rhythm, but of shared breathing, of communal awareness. That kind of silence cannot be imposed; it is built together, and that gives it a uniquely human strength.

The composer may not write that silence into the score, but he presupposes it. Every creator trusts that, before the first sound, there will exist a space in which attention sharpens. The silence before the first bar is a threshold between ordinary life and the suspended time of music. It is a doorway: in crossing it, the external world falls away, and the inner journey of listening begins.

At that threshold, musician and listener are equals. Both are waiting. Both hold their breath. And in that waiting, something extraordinary happens: the promise of the music to come turns, for a few seconds, into a pure form of presence.

Thus, the silence before the first bar is not emptiness but invisible density — the very material from which musical time is built. Perhaps that is why it is one of the truest moments in all of music: because in it, before melody exists, attention, emotion, and the desire to listen already do.

The next time you attend a concert, don’t think about the first sound. Listen to the silence before it. There lies the real beginning — that fragile instant when anything can happen, when music, though not yet sounding, has already begun.